Balochistan occupies the southeastern edge of the Iranian plateau, an area known for being the setting of some of the earliest farming settlements in pre-Indus Valley civilization history. One of the oldest known sites, Mehrgarh, dating back to around 7000 BCE, is located within this region. This places Balochistan at the far western boundary of early civilization. Centuries before the advent of Islam in the 7th century, parts of Balochistan were governed by the Paratarajas, an Indo-Scythian dynasty. Additionally, the Kushan Empire exercised control over parts of Balochistan during different periods.

The Sewa Dynasty, a Hindu dynasty, ruled over portions of Balochistan, particularly in the region of Kalat. The name of the Sibi Division, created from Quetta and Kalat Divisions in 1974, is derived from Rani Sewi, a queen of the Sewa dynasty.

The Brahui people, believed to be among the earliest inhabitants of Balochistan, speak a Dravidian language that has been preserved for millennia. Although Balochistan had an indigenous population during the Stone and Bronze Ages and through the time of Alexander the Great, the Baloch people, who are now the largest ethnic group in the province, did not migrate to the area until the 14th century CE. One theory suggests that the Baloch people are of Median origin.

Islamic Conquests

Islam arrived in Balochistan in 654 CE when Abdulrehman ibn Samrah, the governor of Sistan under the Rashidun Caliphate, led a campaign to quell a revolt in Zaranj (modern-day southern Afghanistan). After suppressing the revolt, the Muslim army advanced into what is now Balochistan, pushing north to conquer Kabul and Ghazni, while another division moved through the Quetta District and seized control of ancient cities like Dawar and Qandabil (now known as Bolan). By 654 CE, most of present-day Balochistan was under the control of the Rashidun Caliphate, with the exception of the fortified mountain town of QaiQan, now Kalat.

During the caliphate of Ali, a rebellion erupted in the Makran region of southern Balochistan. In 663 CE, under the Umayyad Caliph Muawiyah I, the Muslim forces lost control of parts of northeastern Balochistan, including Kalat, following a significant defeat when Haris ibn Marah and a large portion of his army were killed in battle.

Pre-Modern Era

In the 15th century, Mir Chakar Khan Rind became the first Sardar of Balochistan, spanning areas across modern Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. He was a close ally of the Timurid ruler Humayun and was succeeded by the Khanate of Kalat, which initially pledged loyalty to the Mughal Empire. Over time, rulers of Balochistan also aligned themselves with Nader Shah, who granted Kalhora, a Sindh territory that included the Sibi-Kachi region, to the Khanate of Kalat. Ahmad Shah Durrani, the founder of the Afghan Empire, also garnered support from local rulers, with many Baloch fighters joining his army in the Third Battle of Panipat. After the decline of Afghan rule, most of the region reverted to local Baloch control.

Colonial Era

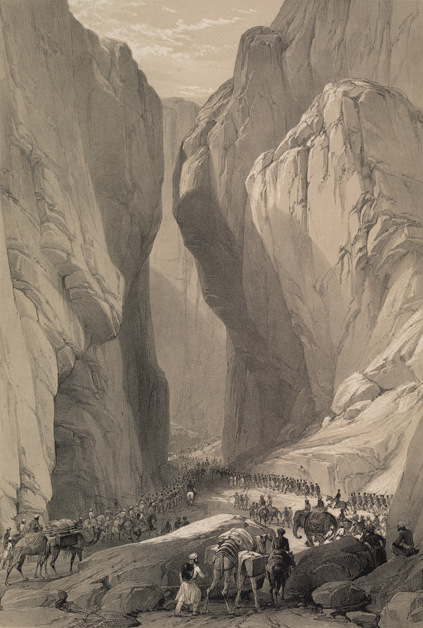

In 1876, northern Balochistan became part of British India. From the fall of the Durrani Empire in 1823, four princely states in Balochistan were recognized and maintained their independence under British protection: Makran, Kharan, Las Bela, and Kalat. The Treaty of Kalat in 1876 formalized this arrangement, bringing these territories under British oversight while allowing them internal autonomy. Following the Second Anglo-Afghan War and the Treaty of Gandamak in 1879, the districts of Quetta, Pishin, Harnai, Sibi, and Thal Chotiali came under British control. In 1883, the British acquired the Bolan Pass, and by 1887, additional areas of Balochistan were integrated into British territory.

In 1893, the Durand Line was established as the boundary between Afghanistan and British-controlled areas, following negotiations between Sir Mortimer Durand and the Afghan Emir, Abdur Rahman Khan. This border still forms the boundary between modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. Two significant earthquakes occurred in Balochistan during British rule: the Quetta earthquake in 1935, which devastated the city, and the 1945 earthquake in the Makran region.

During the Indian independence movement, political dynamics in Balochistan were varied, with parties like the Anjuman-i-Watan Baluchistan advocating for a united India, opposing the partition that ultimately led to the creation of Pakistan.

After Independence

During British rule, Balochistan was divided into a Chief Commissioner’s province and several princely states, including Kalat, Makran, Las Bela, and Kharan. These states eventually became part of Pakistan following the partition of India in 1947. According to the official Pakistani narrative, on 29 June 1947, Balochistan’s Shahi Jirga (a grand council of tribal leaders) and the non-official members of the Quetta Municipality voted unanimously to join Pakistan. However, members from the State of Kalat were excluded from this vote, raising concerns about the legitimacy of the decision.

Qazi Muhammad Isa, then-president of the Balochistan Muslim League, informed Muhammad Ali Jinnah that the Shahi Jirga did not reflect the true will of the people, as the vote only included representatives from British-controlled areas like Quetta, Nasirabad, Nushki, and the Bolan Agency, but not Kalat. On 22 June 1947, the Khan of Kalat received a letter from the Shahi Jirga and tribal leaders from the leased regions of Balochistan, asserting that they should be considered part of the Kalat state rather than British-administered Balochistan. This raised doubts about whether a genuine consensus for accession to Pakistan existed. Political scientist Salman Rafi Sheikh later argued that Balochistan’s integration into Pakistan was not based on widespread support, and that political manipulation played a role, leading to early feelings of disenfranchisement within the province.

Initially seeking independence, the Khan of Kalat eventually agreed to join Pakistan on 27 March 1948, after lengthy negotiations. The signing of the Instrument of Accession by Khan Ahmad Yar Khan sparked dissent within his own family. His brother, Prince Abdul Karim, opposed the decision and led a rebellion against the accession in July 1948. Abdul Karim and his supporters carried out guerilla-style attacks on the Pakistani military in the Dosht-e Jhalawan region until 1950, without significant external support. Despite this revolt, the Khan was allowed to retain his title until Balochistan’s administrative structure was reorganized in 1955.

Baloch nationalist insurgencies have occurred periodically, with uprisings in 1948, 1958–59, 1962–63, and 1973–77. A new wave of insurgency, driven by autonomy-seeking Baloch groups, began in 2003 and is ongoing. While some Baloch demand greater autonomy, most do not support full secession from Pakistan.

In 2015, during a press conference in Quetta, Balochistan’s Home Minister, Sarfraz Bugti, accused Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi of supporting terrorism in the region. Bugti claimed that India’s intelligence agency, RAW, was behind recent attacks on military installations in Smangli and Khalid and was working to undermine the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

Gwadar, a coastal region in Balochistan, was an Omani colony for over a century before Pakistan gained control of it in the 1960s. As a result, many people in the area have Omani heritage.